Walking reflections on good and evil

Interesting meditations during a solo-walk

2/13/20244 min read

Today, I decided to take a walk along the beautiful coastline of Hong Kong Island, facing the skyline and meditating while walking. I opted for a guided meditation to train self-awareness, followed by philosophical meditations, allowing me to reflect on deep topics independently. Recently, I revisited some ancient philosophers, ranging from Socratic philosophers, through Epicurus and the Cynics, to the Stoics and Skeptics. What fascinates me are the striking similarities among these diverse philosophies, rather than their differences. A topic that particularly intrigued me was the concept of good and evil.

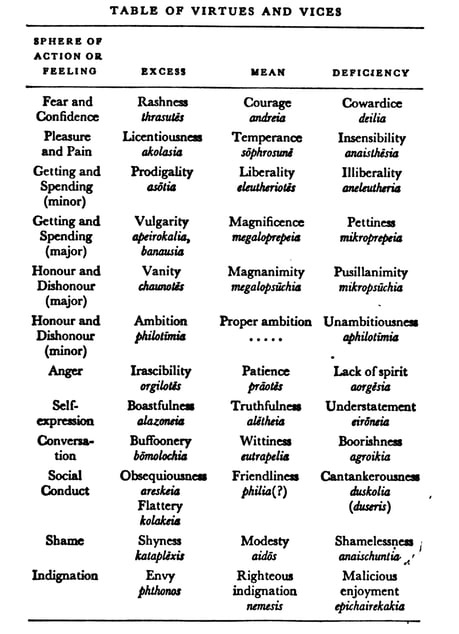

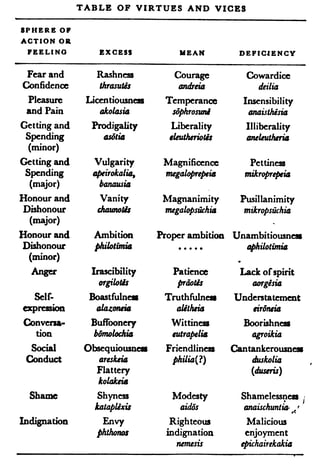

Is there anything intrinsically evil? The Stoics and Aristotelians mostly distinguish between virtues and sins (or vices), rather than good and evil. The Stoics famously identified four virtues: wisdom, justice, courage, and moderation. Aristotle, on the other hand, conceptualized his table of virtuous habits as a ‘golden mean’ between two extremes of sin — one of excess and one of deficiency. Please refer to the table below.

Both Stoic and Aristotelian philosophies advocate for the cultivation of good habits as a means to lead a healthy and fulfilled life. On this point, there is no disagreement, I myself foster building good habits and discipline towards my goals to feel fulfilled. However, I wonder, if someone lacks good habits, is caught in a sinful spiral, or consistently exhibits harmful behaviors, should they be considered unvirtuous or sinful according to their definitions? Nevertheless, if we define living a virtuous life as adhering to virtuous habits, then I can still align with this definition. Digging a bit deeper, what truly troubles me is the misinterpretation of unvirtuous and sinful behaviors as ‘evil.’ I asked friends and family if they thought ‘evil’ exists, and they separately but unanimously answered in the affirmative. Naturally, I asked for examples. The typical responses included major offenses like murderers, rapists, and human traffickers, as well as lesser ones like liars, cheaters, and the immature. We then carefully delved into these definitions to understand the possible reasons behind such behaviors. I’ll spare the macabre details of those conversations, but I’ll try to make my point. Murderers, in cases of legitimate self-defense or defense of family, would not be considered evil according to the definition. My deduction is, if there is a reasonable rationale behind the crime, they would not be categorized as evil. How about other crimes, then? Don’t they all have a reason? The debate heated up here, as motives like ‘crimes of passion,’ ‘jealousy,’ or other petty reasons were clearly insufficient to justify a crime. So, if the ‘primary reason,’ or the most direct cause of a crime, is not considered reasonable, then they were unanimously deemed evil.

As an engineer, I am inclined to look for the root cause of a problem, so I cannot stop at the ‘primary reason,’ as it seems too superficial. Is there a ‘secondary reason’? Or even a tertiary one leading up to the ‘root reason’ behind someone’s behavior? After some difficult moments, which I strive for, as most of the growth is done outside the borders of one’s comfort zone, we got to some interesting conclusions.

Let’s consider the case of the ‘jealousy’ motif. Why is someone jealous? Why does jealousy escalate to the point of driving a person to commit a crime (whatever it may be)? Here, the conversation becomes more complex. Jealousy is a very intricate emotion, often driven by multiple factors. These may include insecurity, low self-esteem, comparison, past experiences, trauma, personal beliefs, attachment style, projection of personal issues, and more. In essence, jealousy is the manifestation of a multitude of underlying issues that are frequently overlooked.

As our discussions delved deeper into hypothetical scenarios, we began losing sight of the initial question: Is there anything intrinsically evil? What initially seemed like a straightforward answer gradually expanded as the conversation progressed, leading to a sense of empathy for the person committing the hypothetical crime. By empathy, I mean a feeling of pity and compassion towards another human being. True, based on Stoic and Aristotelian definitions, such a person might be considered unvirtuous and sinful for not addressing the causes of unvirtuous behavior. However, these behaviors might not be intrinsically evil. They are, instead, strong indicators of deep-rooted human issues. Everyone is responsible for their behavior and its consequences, virtuous or not.

What I am trying to convey in this post is that I don’t believe in the existence of intrinsic evil, but rather in the manifestation of profound human problems. If everyone could introspect, work on the root causes of their flaws, and continuously cultivate good habits for self-improvement, then, hypothetically, evil behaviors would no longer manifest. The reality, however, is much more complex. Not everyone has the tools or self-awareness to confront the abyss within. This is where I find common ground with Epicurus, Aristotle, and Plato: the emphasis on the importance of friends. Friends, like partners, should possess qualities that complement yours, so that friendship becomes a journey of mutual growth through support, help, and teaching.

Self-discovery is not a lonely process.